Let us give up the notion that history is a straight and uncomplicated timeline and instead acknowledge it as a folded structure with at least as much content hidden as open to the light. Behind official events and established names, there lie forgotten and ignored stories. These are no less true than the stories repeatedly told. The exhibition Plissé. Anne-Karin Furunes delves into some of the folds in art history, reveals stories and exposes them to light. The women thus presented in the artist Anne-Karin Furunes’s (b. 1961) large and perforated canvases have created pioneering textile works that are credited with men’s names.

- 1/1

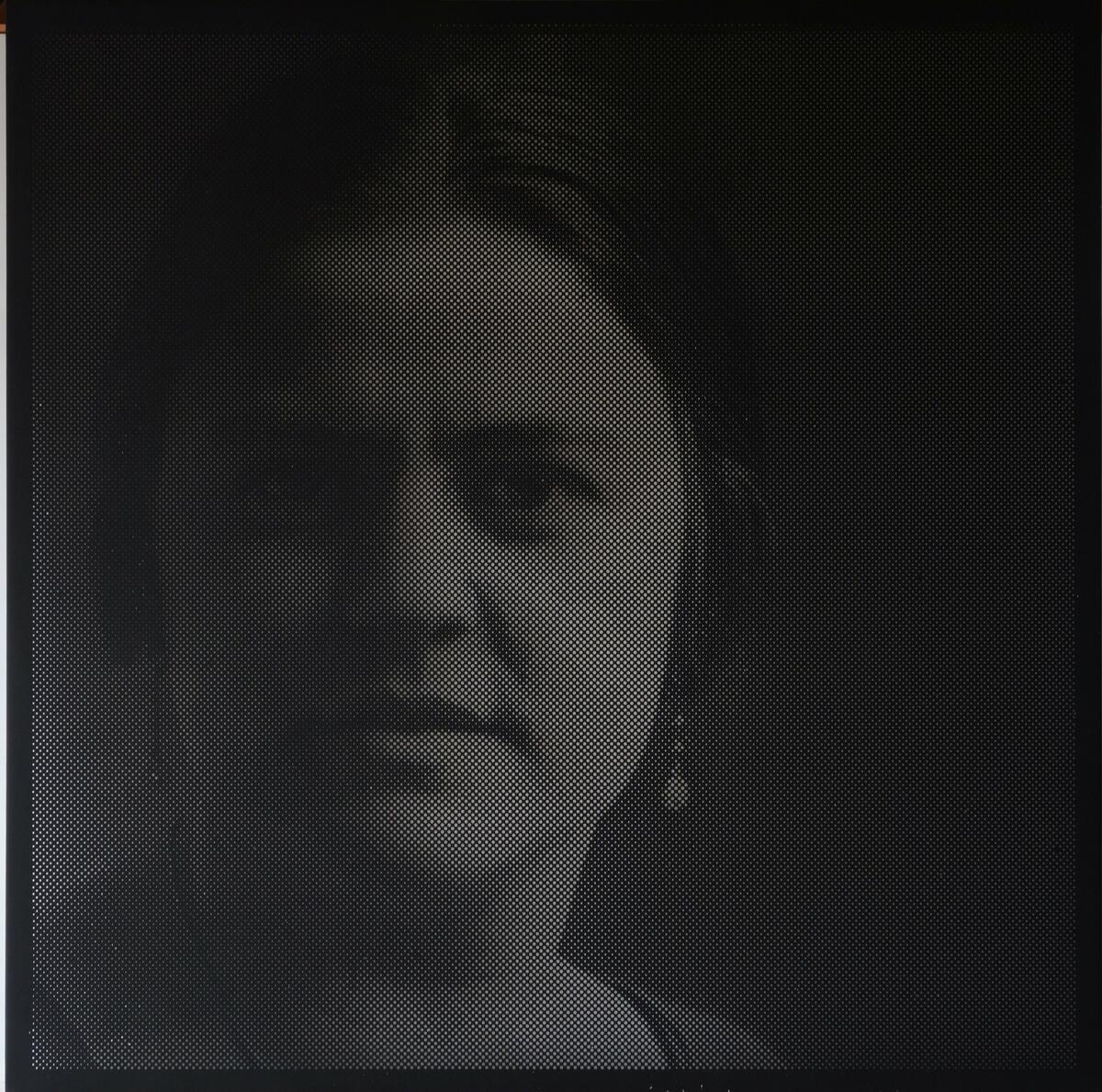

Anne-Karin Furunes, Crystal Images IV, 2013.

The stories about two of the women take place in Venice and Trondheim, respectively, in about the same fold in time. In 1909 the artist and designer Mariano Fortuny submits a patent for a plissé (pleating) machine in his own name, for expediency sake, even though both he and his wife Henriette Nigrin (1877–1965) acknowledge that she is the inventor. The iconic Delphos dress (1907) is the most famous product to result from the innovation; to pleat silk in a way that makes the folds permanent has been impossible before the invention of this new and secret method. The dress gains attention far beyond Italy’s borders and is considered a work of art. In letters, Nigrin reveals that she is the creator of Delphos, not just of the invention that has made it possible. The muse, as she is often called, is far more than an inspiration for the celebrated genius Fortuny.

In Trondheim in 1900, one can read in the newspapers that the jury at the World Exposition in Paris is thrilled with the use of colour in the Norwegian artist Gerhard Munthe’s tapestries. The wool, dyed in a few basic colour values, is combined in varying amounts during carding, before spinning. The result of this unusual method is strands of yarn with a lively play of colours; woven together in pictorial fields, they appear as if they were painted with a brush. Indeed, the fairy-tale scenes are designed by Munthe, but the translation from watercolour to textile is thanks to Augusta Christensen (1852–1923), the hand-picked leader of Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum’s School and Studio of Art Weaving. The tapestries sent to Paris are made by Christensen and her students, and they are awarded a gold medal in the exhibition. The tapestry artist behind the signature GM thus falls under the radar and is largely excluded from art historiography.

Furunes’s monumental portraits present us with women from Venice and Trondheim, depicted more than a century after their textile achievements. The pictures are initially monochrome, either black or white. With tools for making variously-sized holes, she punches out images that are hidden when seen at close range, due to the eye’s lack of overview. When seen at a distance, and in combination with the viewer’s body movements, the background shines through and becomes part of the images – created precisely by the absence the holes supply, but also by light. The light in the room – right now – merges with the individuating features in the faces and reinforces their personal presence. They are animated; here is Augusta Christensen. Here is Giorgia Clementi, who wove textiles in Fortuny’s studio, and here are her colleagues whose names are no longer known. Henriette Nigrin, for her part, is represented by the dress Delphos, which in the exhibition becomes her portrait. In Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum’s collection, it has until very recently been attributed to Mariano Fortuny. If we enter the cavern inside the cavern and allow light to filter through the perforations, straightforward truths become complicated.

In Plissé, a vibrating encounter between strong individuals takes place; their stories are played out on a surface that is now folded out. It has a multitude of facets and is so much larger than what has previously been laid out. Several time periods exist simultaneously in the room, like colour values spun together in a strand of yarn; the moment the women were photographed underlies the time-consuming work which Furunes has invested in bringing them again to light. Outside this, in turn, is the viewer’s here and now. In the unique framework of Stiftsgården (the royal residence in Trondheim), with ornate stucco ceiling décor and crystal prisms refracting and dispersing light in a thousand directions, the portraits and the silk dress become imbedded in your memory of sensations.

The philosopher Deleuze writes about two related ‘infinities’ – folds in matter and folds in the soul. Objects and thoughts are intertwined. A dress is not merely a textile object; it is at the same time folded into stories about clothing and textiles, fashion and technology, social identity and complex societal structures. It is what happens between the things and the ideas, in the form of never-ending events, which is the essence of the world.

In Furunes’s portraits, individual lives are immortalised and remain with the viewer as after-images on the retina. The women’s gazes, for their part, continue beyond the room’s walls, out the windows, through the city and over the mountains. The strands of fibre are woven and fastened – but never cut.

Curator Solveig Lønmo