- 1/1

Global warming and the natural catastrophes to which it leads constitute some of the greatest challenges human beings face. In our attempt to exploit and control nature, we have gone too far. Before the Enlightenment’s romanticisation of the experience of nature, people saw uncultivated nature as something dangerous and threatening. Nature was not a place for recreation and aesthetic enjoyment. In the 1700s, Europeans’ view of nature started changing. The French Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) wrote about the joy of walking in the mountains and seeing beautiful nature in combination with sudden surprises such as unexpected villages or ruins. This can be seen as the dawn of nature tourism.

Today, recreation and the enjoyment of nature are important free-time activities. We dream of wandering undisturbed in wild mountain scenery, but this is now only a dream and an illusion. Our image of what we consider to be pure nature probably has more man-made elements than we like to believe. Cabins and alpine farms melt together with forests and mountains. Can it be that our actual enjoyment of nature depends on culture being close enough at hand to give us a certain sense of control and safety when we encounter what is wild and unknown?

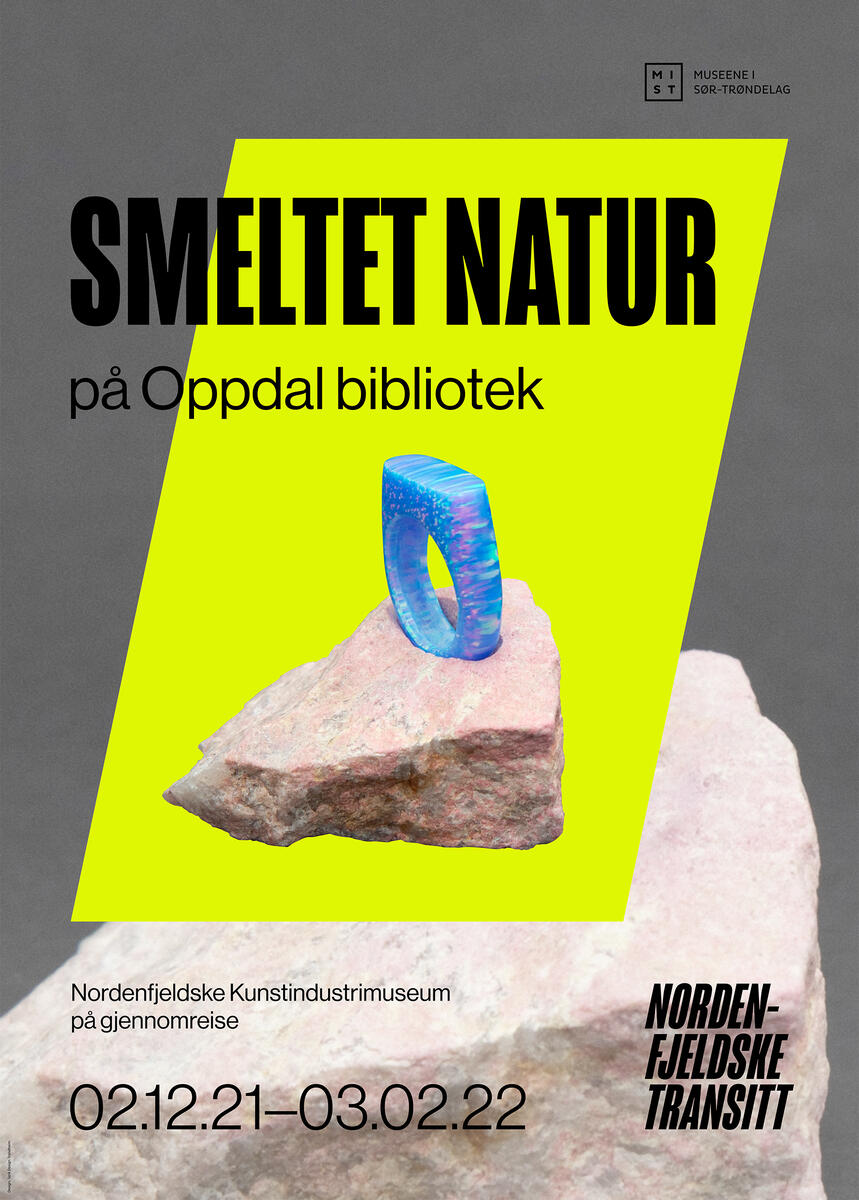

It is in our nature to form the environment with our culture. It is therefore ironic that many people become more uncertain when coming across manmade things – art, for instance – than things in nature. Why do we relate differently to a stone in the mountains than to a stone lodged in a cracked clay pot? The platter with red and white glaze is locally sourced. The glaze is made of feldspar from Finnmark, and the pattern is pressed in with straw from Jæren. It is made of molten stone. Is the blue ring on the stone podium less natural because it is made of a synthetic material that resembles stone? Is a stone cup that cannot be used still a cup?