- 1/1

The history of ceramics stretches back thousands of years. Although ceramic works are easy to break, many ancient objects still look like they did when they were first made. The colours and frequently fantastic patterns and motifs endure for millennia. The ceramic objects around us thus represent connections to earlier times.

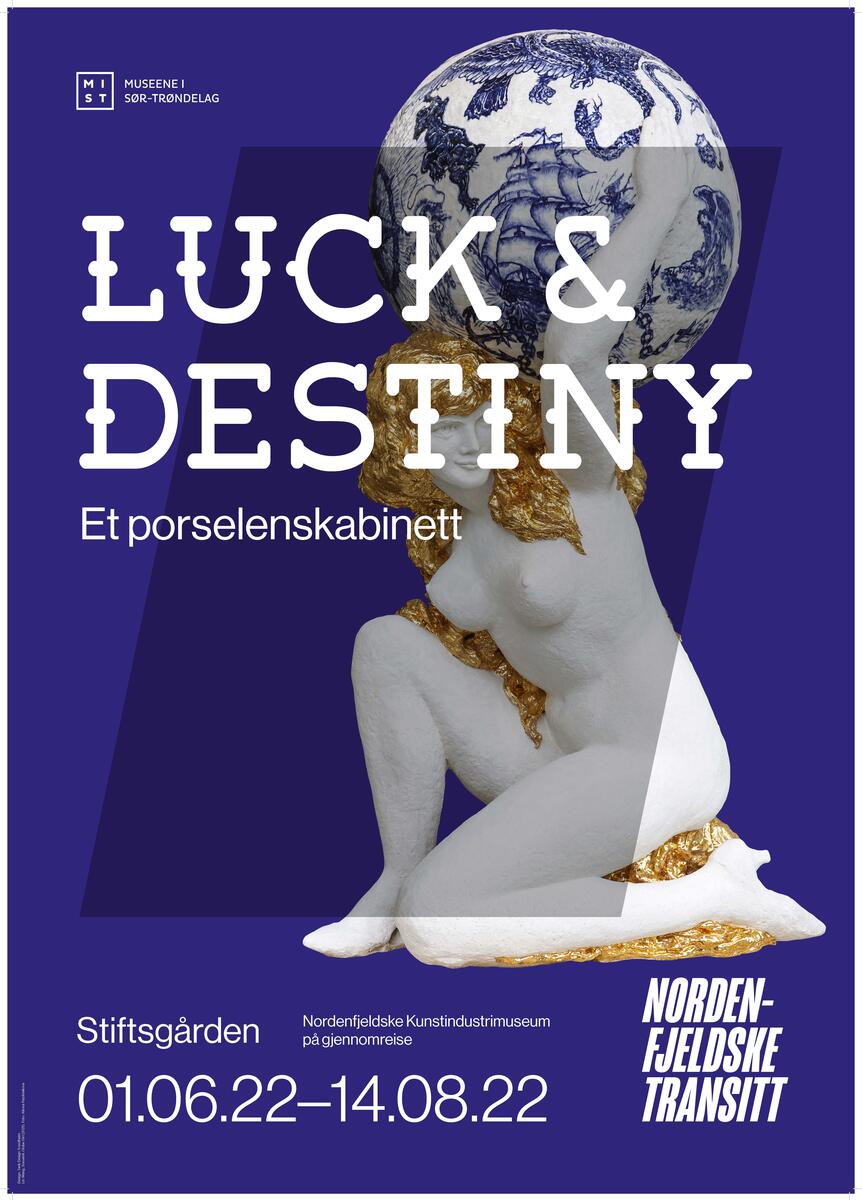

They also link us to other places. The European history of porcelain is defined by journeys across the ocean and by a fascination for things distant and unknown. While the Chinese had produced porcelain – the hard, glass-like ware made of kaolinite clay mixed with minerals – since the Han Dynasty (25–200 AD), the recipe for making it was an unsolved riddle for Europeans until the early 1700s. In the meantime, ‘the white gold’ represented something unachievable. European ceramicists drew inspiration from the forms and glazed motifs of Chinese porcelain vases and made imitations in faience (earthenware). The so-called ‘chinoiserie’ thus represent both mania and misunderstanding. The porcelain exported from China – objects often made specifically for the European market and taste – were sent to Europe in the 1600s via trading companies such as the Dutch East India Company. Teacups with handles and noble coats of arms were commissioned – and the customers were both rich and demanding.

When the original 18th-century wallpapers in the room now called The Chinese Cabinet were restored in 2017, the theory was launched that this room could originally have been a porcelain cabinet. The painted wall motifs show an Eastern landscape seen through a Western lens; Chinese gardens are interpreted in a European rococo style. Mrs Schøller (1720–1786), being the well-travelled noblewoman she was, probably owned valuable Chinese porcelain as well as modern German Meissen porcelain. When she commissioned the building of Stiftsgården (1778), it was still more than a century before porcelain production began here in Norway (1887). The room must have been a demonstration of both cultural and financial capital, and it may have kindled envy amongst those who only owned simpler ceramic goods and who had never been abroad. But if they were invited to Stiftsgården as guests, the Chinese cabinet would have sent their imagination sailing to distant lands. The tea they were served in porcelain cups and the scent of the oranges in Mrs Schøller’s orangery would have contributed also.