Magic is something we today associate with illusionist entertainment and children’s games, but we can also describe children’s play and certain experiences of nature and art as magical. In a world that emphasises rationality and efficiency, our relation to magic is ambiguous. We live in a society obsessed with measurement and quantification, but what about the things that cannot be counted or measured? The sociologist Arnaud Gaillard argues that with the concept of magic, we can describe something intangible about our own reality:

As human beings, the need to devise a rational explanation for everything in life is similar to the temptation to understand every trick of a magic show. Whereas, in both cases the true interest is more about the surprise caused by what is not controlled, that is the beauty of what remains mysterious.

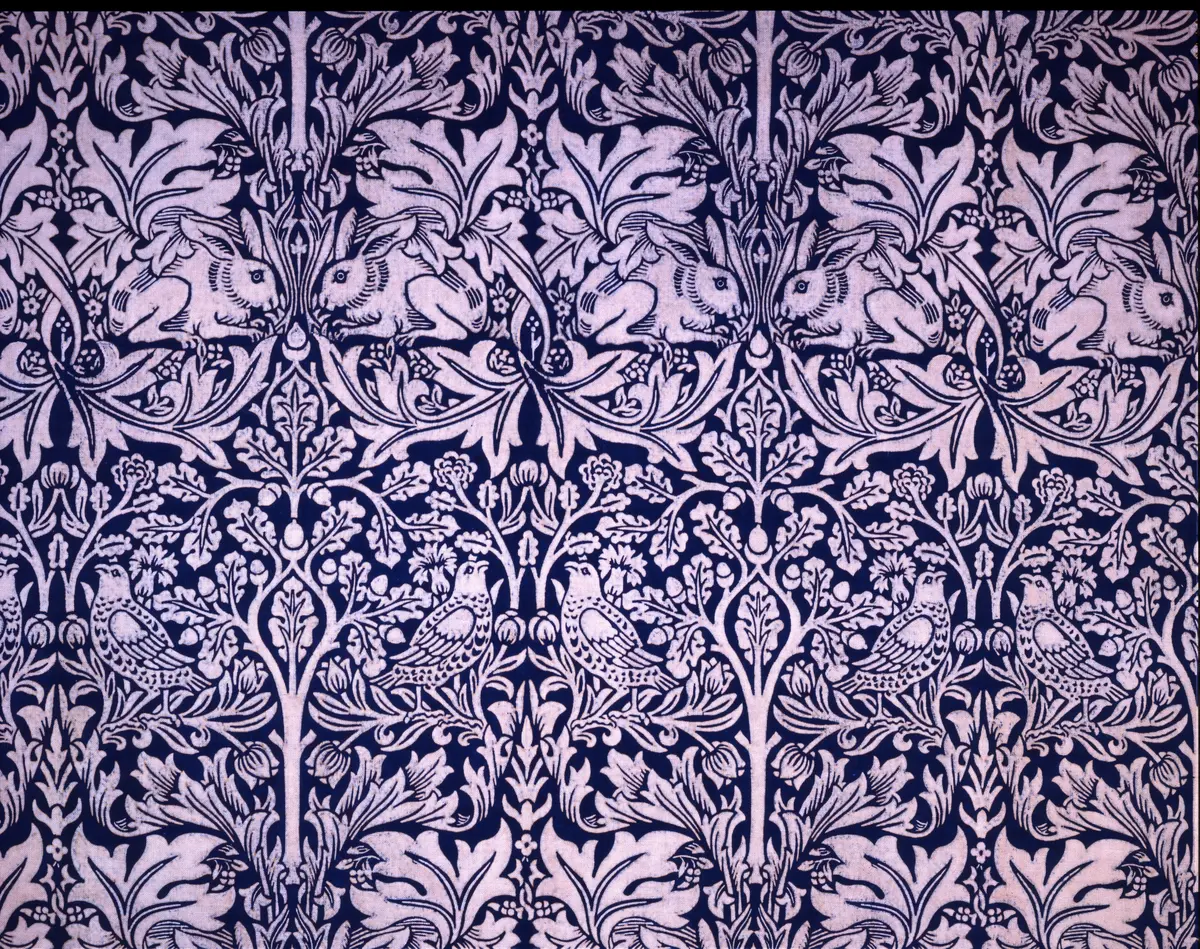

The beauty in what we cannot explain, in what remains a mystery to us, is a theme we can find in many works in this exhibition, one example being Tom Kosmo’s Domestication, in which we encounter anthropomorphic presentations of animals in folded or draped human clothing. Another example is Bjørn Båsen’s Tchaikovsky Cabinet, which is a hybrid object: both a painting and a piece of furniture. Båsen himself calls it a ‘painting cabinet’ (maleriskap). Mystery is emphasised by the motif on the cabinet’s front. What is hiding in the dark depths under the waterlilies?

In the rift between the rational and the magical, the witch has become an important feminist symbol. The witch is antiauthoritarian and critical of society. She defies the boundaries of what society tolerates and has become a symbol for those who are marginalised and persecuted. In Ask Bjørlo’s Witch Compass (Heksekompass), witches fly in each their own direction and also symbolise the four elements earth (north), air (east), fire (south) and water (west). In the centre is a glittering moon, which Bjørlo sees as a fifth element representing the soul. The sculpture can bring to mind a weathercock or a church spire. This is the artist’s nod to Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim and role the city played in witch trials in Norway (1500s–1600s).

The works in the exhibition Reenchanted are included precisely because they suggest something strange or uncanny, sensory, monstrous, lush and fantastic.

The starting points for Málfríður Aðalsteinsdóttir’s embroideries are geometric shapes in church cupolas in Rome. The works represent a view of architecture and a time period in which spatial forms and the use of numbers had religious and symbolic meaning. Kristine Fornes’s work Djevelen fra Oslo / The Devil from Oslo (2015) also enables the telling of stories hidden behind majestic church architecture.